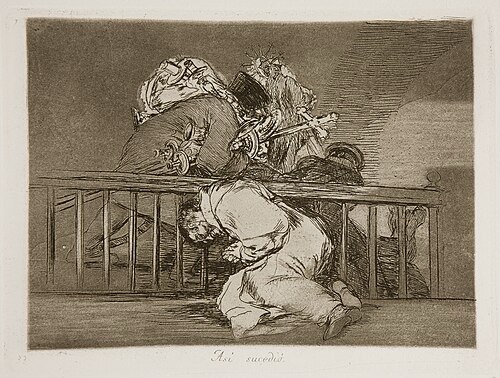

Así sucedió by Francisco de Goya

[Manuscript from a talk delivered at the centennial celebration of Foucault at Philosophy, Disability, and Social Change 6]

Introduction:

For the past two years, my focus has been investigating what my friends and I have described as “eugenic modernity.” I have examined this, first, from the position of neoliberalism and biopolitics, then from the state of exception and political decision. Now I would like to extend this analysis to something more general – to the democratic principles operating within democracies. However, I want to focus on one thinker whose specter, alongside those of Hobbes, Spinoza, and others, hangs over us – Jean-Jacques Rousseau. Rousseau’s entire philosophical project, and I mean this without a hint of overstatement, is representative of the fundamental transformations that took place at the advent of bourgeois democracies. In a lecture given in Brazil in 1976 called the “Mesh of Power”, Foucault laments the “Rousseauification” of Marx by revolutionaries of the nineteenth century and his own. I will argue that—alongside Hobbes, Marcuse, Freud—one of Foucault’s primary targets in The History of Sexuality is, in fact, Rousseau and—to be more blunt—the democratic tradition that heralds the social contract. Foucault shows us that recourse to “democratic principles” in the face of our eugenic condition actually strengthens it. It will take an evacuation of those claims to legitimacy as well to understand where we are, and how we got here.

We can and should pursue this criticism and reveal that Rousseau’s political ontology is explicitly one of social defense and what I will call biopolitical absolutism – and that those clinging to its principles are clinging to the predicates of eugenic modernity. Rousseau trades absolute monarchism for a biopolitical absolutism that makes the function of the state explicitly aligned with the government of disability. The emergence of constitutions and “social right” correlates exactly with the vitalization of massacre that Foucault speaks of in the fifth part of history of sexuality and his lecture series “Society Must Be Defended”.

From Rousseau’s political economy, to his pedagogy, to his Social Contract. The explicit element that must be protected is the human being’s perfectability. Rather than treating this as an innocuous term, we have to understand that this teleological-developmental conception of the human being and its capacities is central to Rousseau. Alongside the human’s perfectability (which is still certainly the goal of the longtermists, the “don’t die” technohumanists, and their posthumanist counterparts), there is the human’s risk of “imbecility” which, again, should not be simply treated as an offhand ableist remark from a French essayist, but instead as an utterance made possible by the discursive formations surrounding the democratic-revolutionary milieu of the eighteenth century. We must also remember that, for Foucault, the French Revolution is as much an epistemic event as it is any other kind of rupture. And that is why, in Madness and Civilization, Discipline & Punish, as well as The History of Sexuality, the fall of the Ancien Regime comes with the emergence of the disciplines and biopolitics. These are transformations that take place in a democratic-revolutionary context, and become the very basis of the new counterinsurgencies that have pierced so deep into what we consider to be everyday life.

Rousseau sits at the threshold of biopolitics. How this will be articulated is somewhat schematic:

First, what will be examined is precisely how Rousseau lays out his political ontology, how he transfers sovereignty to the social body (through the general will) and how this lines up, line by line, the biopolitical transformation that Foucault articulates in Part V of the first volume of his History of Sexuality. Ultimately, what Rousseau is searching for is naturalized basis for the legitimacy of power.

Second, once one has a grasp on the constituent parts of Rousseau’s biopolitical ontology, the function of the sovereign (which is now transformed) must be examined. First, the basis of the right to punish is laid out explicitly in biopolitical terms, and the same step by step analysis will be necessary. Second, the hailed essay on the origins of inequality actually reveals to us just as much about this diffuse social sovereign as his social contract or texts on political economy. It is precisely through the interplay between perfectability and imbecility (which is what is at stake in amour propre, when read honestly and carefully), that governance becomes explicitly a question of disability. Through its function expressing the general will and maximizing the forces that underwrite it, government becomes a government of disability.

Finally (if time permits), I would like to address why, right before Foucault ends his 1976 lecture series with the introduction of biopolitics, he spends two lectures discussing the emergence of the notion of constituent power and the bourgeois concept of the constitution. I believe this analysis of the forces that compose the social body, their leveraging, their protection – these are what (so-called “radical”) democrats constantly call on to overturn our age. But in fact, those are the very things that place us in the epistemic gaze of biopolitics and the machine of discipline.

Rousseau’s biopolitical ontology:

Rousseau’s volonte generale, is a largely misunderstood notion, often reduced to a will of all – which is not what it is. The general will is a force that is “always right” and aligns with “utilite publique” (Basic Political Writings 172). What is in the interest of public utility is what is at stake in the general will. The will of all can be erroneous, the general will can never err – because the maximization of utility is always the arrow of progress. This is of course the basis of the first principle of the Declaration of the Rights of Man (“Les distinctions sociales ne peuvent être fondées que sur l’utilité commune.”) Inequality always has to track with common utility.

The general will, however, is inexpressible without a sovereign, which is equally inalienable. Rousseau’s system, which still informs how we conceive of political activity today, is bipolar. On the pole of the “public person” you have two entities. On the one hand, you have the sovereign (which is the arbiter of the general will, and has lawgiving power) and on the other you have the state, which regulates and disciplines subjects. Then there is the other pole, which is itself also bifurcated. This bifurcation is still central to our understanding of the political subject today; on the one hand, you have the citizen – who is the vital base of the sovereign and participates in sovereign power. But then you have the subject, who is regulated and punished by the state. Of course, just like we never see constituent power, we only see police, we never really experience “citizenship” except through our position as a subject (we are regulated by police, and read our malleable and meaningless “rights” in custody). This distinction between citizen and subject must be thoroughly emphasized, because it is the same distinction that thinkers like Agamben rightfully believe is a signature across the history of Western politics that makes everything from homo sacer to the Muselmann possible. For Rousseau, subject means pure subjection to the state, one is a subject explicitly when their bare life is in the hands of the state. This distinction is the same in Marx between citizen and man. It is for the Sovereign to make recourse to the citizen precisely when it is seeking out the regulation and destruction of subjects.

Not only is this multitude transformed, but every individual is, themselves, transformed. Each individual is not just contracting with the sovereign, but with themselves as a member of the sovereign and, equally as important, as an object of the state. This bifurcation of the human being is necessary to protect what Rousseau calls the social right.

This becomes clear when one sees how the right to punish manifests in Rousseau. We will examine one small passage from chapter V of book II, on the right of life or death, very closely:

“Whoever wishes to preserve his life at the expense of others should also give it up for them when necessary. For the citizen is no longer judge of the peril to which the law wishes him to expose himself, and when the prince has said to him, “It is expedient for the state that you should die,” he should die. Because it is under this condition alone that he has lived in security up to then, and because his life is no longer only a kindness of nature, but a conditional gift of the state.” (176-177).

What is happening here is a delicate presentation of the inhumanity of the subject at the moment of judgement. First, it must be noted that the transformation of life into that which is a conditional gift of the state is the very condition that defines biopolitics as an ontology. The simple fact of living is now determined by, not one’s supposed “citizenship,” but one’s subjection or subjecthood in relation to the state. And this “gift” can be taken away not out of a reason of transgression necessarily (like in the Hobbesian model or in Pufendorf’s) but out of expedience… or utility. Rousseau writes in his article on Political Economy that “It is from the first moment of life that one must learn to deserve to live” (138). Poor Emile.

By being a citizen and subject, one is always at risk of losing their membership in the state, and therefore being put to death as an enemy. A public enemy is “not a moral person [personne morale, i.e. a citizen or political individual], but a man, and in this situation the right of war is to kill the vanquished” (177). One is reduced to bare life, and eliminated not as a citizen, but as a man.

But a further change in the right to punish must also be examined. As Foucault delineates in Part V of the first volume of the history of sexuality, punishment and execution is no longer a “right of rejoinder” or a right of “seizure” of life, like the seizure of goods or things (HoS1 135-136). Sovereignty now has the explicit aim of multiplying, organizing, and optimizing the forces of life. The sovereign no longer refers to itself as the auto-legitimizing object of its right to lay waste, but instead refers to the “social right”, a social right which, of course, only it can express. This new reasoning of execution “is now manifested as simply the reverse of the right of the social body to ensure, maintain, or develop its life” (136).

Rousseau’s account of the right to punish is, to the letter, an expression of this new explicitly biopolitical mode of punishment. “[E]very malefactor who attacks the social right, becomes through his transgressions a rebel and a traitor of the homeland” (Basic Political Writings 177). Furthermore, the biopolitical justification of the condemnation of the individual is also laid out clearly. One is only put to death if one “cannot be preserved without danger”. It is not simply that they transgress, because there “is no wicked man who could not be made good for something,” who could not serve public utility. One is, as Foucault would say, put to death because they pose a danger:

Hence capital punishment could not be maintained except by invoking less the enormity of the crime itself than the monstrosity of the criminal, his incorrigibility, and the safeguard of society. One had the right to kill those who represented a kind of biological danger to society. (138)

Massacres are vital, it is for the sake of all of us that someone is killed, for the objective utility that is the general will. For “all justice comes from God” (Chapter 6, Book II of Social Contract) and the “most general will is always the most just and that the voice of the populace is, in effect, the voice of God” (Discourse on Political Economy 127). The biosecurity of humanity has always been a question of secular deliverance.

Rousseau has dissolved the absolute power of the monarch, with their right to kill, and replaced it with a biopolitical absolutism with its diffuse social right to life which makes it necessary to kill. Furthermore, this is part of why Foucault could say on February 1st, 1978, that for Rousseau “sovereignty is not eliminated; on the contrary, it is made more acute than ever” (Security, Territory, Population 107). Rousseau diffuses sovereign power into the population, and its defense becomes the primary claim of the sovereign. These quiet metaphysical maneuvers are what make executions increasingly rare, but we have no reason to celebrate as eugenic and genocidal violence emerges in their place.

Rousseau’s Government of Disability

It is with this in mind that we must come to the problematization of disability. Ability is a focal point with which Rousseau’s anthropology, as well as his governmentality, becomes legible. Ableism is a mode of world disclosure and a grid of intelligibility as much as it is anything else. I have stated this elsewhere before, but it is always worth repeating. And this is very much the case in Rousseau’s notion of government. Rousseau’s anthropology and Rousseau’s theory of government dovetail at the point of capacity. It is through the constitution of a civil state that…

[A human’s] faculties are exercised and developed, his ideas are broadened, his feelings are ennobled, his entire soul is elevated to such a height that, if the abuse of this new condition did not often lower his condition to beneath the level he left, he ought constantly to bless the happy moment that tore him away from it forever and that transformed him from a stupid, limited animal into an intelligent being and a man (167).

It is through constituting a civil state that a human being becomes an “intelligent being and a man”. The constituent point at which one becomes citizen and subject, is also an anthropogenic event where the human being shamefully drapes over its inhumanity by gaining its participation in sovereignty. It is in this instance, outside of time but nonetheless present, of the constitution of society that faculties are exercised. The human being is a human being inasmuch as it is governed and governable. As we have already shown, however, this status is always placed at risk in the defense of the social body.

Though the human being has gone through this beautiful theodicy of social life, it is still always ailing with a unique problem: imbecility. Rousseau asks “why is man alone subject to becoming an imbecile?” Now, this term needs to be treated with the juridico-medical specificity with which Rousseau would be treating it in the late eighteenth century. The human alone is subject to degeneration. Luckily, the human being also has a teleological aspect: perfectability. Old age and accidents result in a man losing “his perfectability” that enabled him to acquire all those ennobled feelings and faculties. This inherently refinable being, who is always at risk of degenerating into an “imbecile”, is the protagonist of Rousseau’s Discourse On Inequality. The problem of moral inequality is precisely that it degenerates the human being, and, perhaps just a bad for Rousseau, makes it possible for an “imbecile to lead a wise man” (92). However, there is another, frankly uncommented on, aspect that needs to be examined: that is, where natural inequality exists. For Rousseau, inequality is “practically non-existent in the state of nature”. The problem of inequality is only possible in a world which already has law and property. Rousseau attests that “it follows that inequality in status, authorized by positive right alone, is contrary to natural right whenever it is not combined in the same proportion with physical inequality” (91). The problem that the general will, democracy, faces is that it produces an unnatural inequality. This is where a sovereign that is true to the direction of the general will must intervene. Moral equality must be enforced, and replace natural equality in the state of nature, so that unnatural inequality comes to light, and prevents the “imbeciles” from taking the reins from wise men. The whole problematic of Discourse on Inequality is that Rousseau contests that moral inequality is indicative of natural inequality, that is what is lamentable in the Ancien Regime. In a properly administered world, where amour propre is suppressed in favor of the perfectability of the species, the sovereign would be properly expressing the general will. The general will is always aligned with the refinement of the species, the promotion of human capacity, and the preclusion of disability. All that risks this mission is a danger that is counter to the social right and must be treated accordingly. The vanquished are killed because they are unoptimized an incongruent with the teleological perfection of the species. But don’t worry, the general will is always right.

Conclusion: Constituent Biopower

I want to conclude by provoking a question. Why is it that Foucault spends two lectures discussing constitutional and constituent theory before introducing biopolitics? On March 10th, 1976, Foucault spends an hour discussing the Rousseauian constitutional theorist Emmanuel Joseph Sieyes and his theory of the third estate.

The third estate is simply all of the constituent elements of a social body that Sieyes believes exist even prior to the constitution of a sovereign. “What does”, Foucault says, “constitute the strength of a nation is now something like its capacities, its potentialities”. It is the identification, ordering, and refining of these capacities that then becomes the mission of the sovereign in the biopolitical epoch.

These virtualities, which take the name of capacities, perfectability, etc. are the object of the government of disability. As long as thought coincides with the affirmation of the objects of biopolitics it will perpetually serve it.