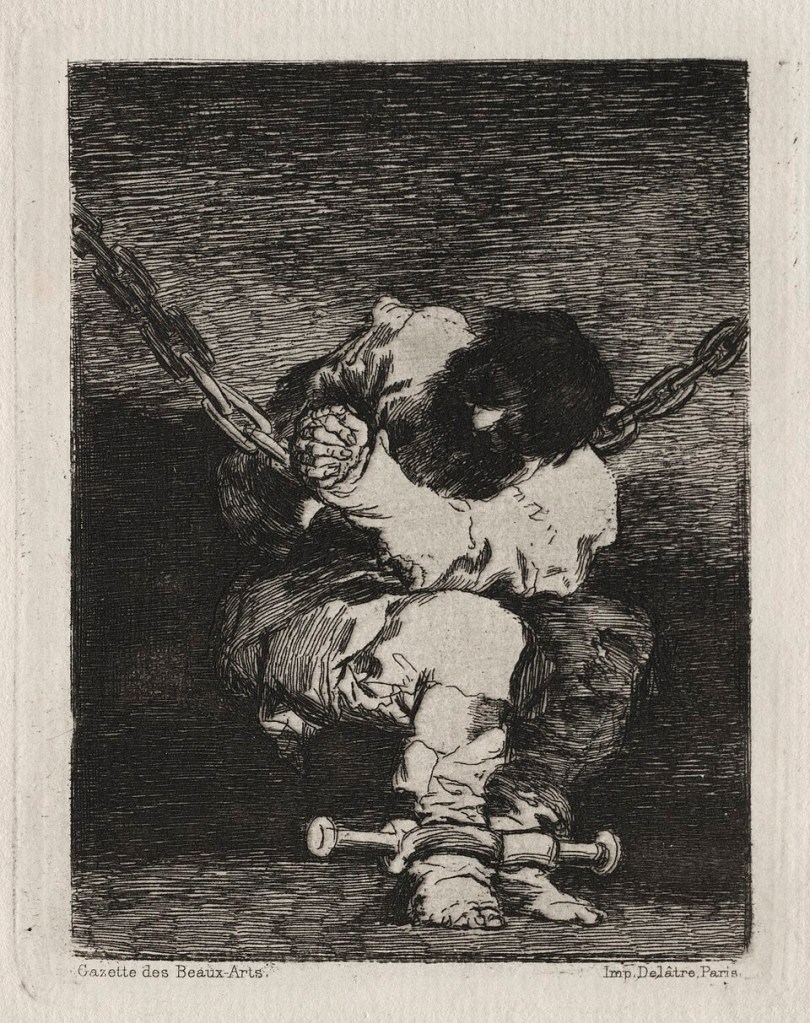

Tan bárbara la seguridad como el delito (Security as Barbaric as Crime)

In Foucault’s consequential lecture series written at the height of the formative time in his development of genealogy, “Society Must Be Defended”, there is a short interlude that demands some meditation – especially in our time.There was a moment, in that constant war of political philosophy in the Early Modern period, where Homo oeconomicus was, momentarily, set aside. A new figure emerged against (and beside) the “noble savage” of contractarian thought. The tension between these two characters reveals something essential about discourses on power that remains somewhat elusive to us.

Hobbes’ de-historicizing of the question of Right and Henri Boulainvilliers’ response to parlementaire historiographers are where we must begin. We must only make note of one thing as it pertains to Hobbes. Hobbes’s method functions within the conquest and contestation of right happening the battlefields of knowledge and power-relations to quiet the guns, eternally. The compact, whether one gives it its ground in right reason in De Cive or Authorization in Leviathan, puts to rest the clattering of guns and of history. This helps us understand the bifurcation on the frontispiece of Leviathan. With one discursive move, given the name Sovereign Right, both battles taking place are supposedly silenced:

“That is of course why the philosophy of right subsequently rewarded Hobbes with the senatorial title of “the father of political philosophy.” When the State capitol was in danger, a goose woke up the sleeping philosophers. It was Hobbes.” (Society Must Be Defended, 99).

It is a question of excising the risk of a discourse on history. The human being and its commonwealth, which itself excises civil war, precludes the necessity of any historical claim. But there are other discursive tactics in the long great game of violence.

Boulainvilliers, faced with a similar contestation—and also a part of the broader aristocratic reaction to historical claims of “public right”—looks elsewhere. To Boulainvilliers, there indeed can be a use of historical knowledge to ground power. The nobiliary reaction must, for Boulainvilliers, use history or a mode of historical intelligibility of a given political situation to understand the “primitive spirit of a government” and render apparent a “state of affairs that was a state of force in its primal rightness.” By doing this, modern customs find their “true origins” (191-192).

What must be established, then, is what Foucault calls the “constituent point”. Foucault names it that so as to “avoid without erasing” the word “constitution.” This constituent moment is not reducible to a juridical covenant “at some point in time—or architime—had been established” (192). The discovery of the “constituent point” functions differently. It is to “rediscover something that has its own consistency” and “it is not so much of the order of law as the order of force, not so much of the order of the written word as of the order of an equilibrium.” Foucault urges us to seriously consider the medical (and military) use of the word constitution. It relates to the overall equilibrium of the body and its forces.

Of course, we have to return to Hippocrates. Constitution, krasis, describes the general composition of the body and its forces. In his Regimen, Hippocrates instructs his physicians to acquire an understanding of “the original constitution of a man” before intensifying any regimen (Regimen I, XXXII). This means, plainly, not to overexert the patient at first, so as to establish the originary nature of their physiological state. Once again, one finds the pressing need to articulate the contours of the quiet history that formed a connection between constituent power and the management of life in eugenic modernity.

With this expanded, non-juridical, and dynamic conception of constitution, a different kind of history is needed. Foucault writes that once “constitution no longer meant a juridical armature […] but a relationship of force, it was quite obvious that such a relationship of force could not be reestablished on the basis of nothing” (193). This medical conception of constitution defined by a relationship of force “reintroduces something resembling a cyclical philosophy of history”. By linking together “constitution and revolution” in this way, one is lending a new constituent ground to power.[1]

This new cyclical philosophy of history, like any recurrence, must not just thwart off a founding juridical basis, but also that “natural man who existed before society” (194). This history has no place for the “savage” of the contractarians “noble or otherwise”. What Boulainvilliers is “trying to ward off is both the savage who emerges” explicitly to “enter into a contract and, and the savage Homo economicus whose life is devoted to exchange and barter”. This naturally exchanging figure is the basis of the juridical conception of constitution, which Boulainvilliers believes he is expanding. The “exchanger” is “basic to juridical thought” precisely because in exchanging rights one founds a sovereign, and in exchanging goods one constitutes a social and economic body. “Boulainvilliers creates another figure, and he is the antithesis of the savage” (195). This figure is the barbarian.

The barbarian is the negative image of the “noble savage” and Homo economicus. This supposed savage of the jurists and anthropologists is that figure who tacitly consented or entered into civil society, taking on its predicates and ceasing to be a savage. The barbarian, by contrast, “is someone who can be understood, characterized, and defined only by the fact that he exists outside of it. There can be no barbarian unless an island of civilization exists”. The barbarian is at the city walls, crashing against them. Unlike the noble savage, the barbarian does not make entrance into history by exchanging their way to the founding of a society, “but by penetrating a civilization, setting it ablaze and destroying it.” However, there is one crucial thing that both of these figures have in common. They are equally “elementary” (195).

What the introduction of the figure of the barbarian brings to the discourse on civilization is its indeterminant etiology, a historical boundlessness. Its indeterminacy is, in fact, its foundation. It produces something stronger than a singular historical event or sovereign text. Unlike the “noble savage” of the contractarian, who enters into civilization through “natural” trade, the constituent point that the barbarian presents is entirely different – and it opens history into a cyclical field. The barbarian constitutes the ever-present “outside of civilization” and the ever-present risk of its destruction and dissolution. The savage was the great “adversary” of Boulainvilliers and his successors because they constituted an element that could give rise to society, rather than a piece of evidence that motions to a primordiality.

To Boulainvilliers, this figure produced a “humanity without a past” – motivated by self-interest in the production of society (it is worth noting Boulainvilliers translated Spinoza’s Political Treatise into French). The “social,” under this strategy, manifests perpetually though active genesis. Like all liturgies, it is a dynamic practice that makes present its own conditions of coming into presence.

What the barbarian allows is the co-constitution of society with that which endangers it, and it saps the historian of anything that “exists before the social body”. If the good and noble savage was the figure that naturalized the “prosocial” impulse and genesis of society, the barbarian is the figure who gives it an endless dominion and an ever-present external threat, the constituent power that lends credence to any and all exceptions. Society and its defense share a temporality and a theoretical birth.

With Homo oeconomicus, society is that which must be defended; with the barbarian, society is defense as such. Society becomes what has always already been defended and is always under threat. These oppositional figures constitute two poles upon which we can say the triumph of civilization tends toward lacking nothing (as our friends who made a Call did not so long ago). They are opposed, yet become complementary once the eugenic teeth of “the social” are bared.

Civilization, through the notion of “society”, closes in on itself, donning itself in both its historical necessity and fragility. It could never be otherwise, and yet all must be enlisted and mobilized to ensure this is the case. This brilliant counterinsurgent double maneuver towers over life.

The barbarian carries with it power’s admission of the quiet anarchy it both claims to have vanquished and desperately needs.

[1] Long before Antonio Negri conceived of his exhausting archive, Il potere constituente, Foucault had already revealed both the counterinsurgent and eugenic bases of this fiction. For Michael Hardt to mendaciously title the English translation Insurgencies, speaks only to the counterinsurgent nature of many so-called Foucauldians in the anglosphere.