Maurice Blanchot, in his excursus on friendship, is brief, tactfully so. Blanchot is an author who can make of brevity a tool for opening expanses. Blanchot’s mastery of the aphoristic form exemplifies this, but even in his more conventional prose one finds where he restrains himself the most to be the most pensive. His essay, “Friendship,” is no exception.

Blanchot’s essay is one about death. It is about the death of his enigmatic literary hero and friend, who Blanchot and so many others owed so much, Georges Bataille. And while it is about death, it is not about loss; at least not in the conventional, substantial, sense. It is, in fact, about a malignant acquisition that comes with death, with the collapse of a friendship, with the falling out of love.

Friendship is that intimacy that arises out of a unshared unintelligiblity, which comes and goes. And it is precisely this that makes the end of a friendship so crushing, because it turns what was a form of life into an account.

We are called forth to remember who we love, or loved, devoid of that intimate distance – it is now simply a point of relation in a socialized network. It is now something shared, played out in history and our subject function. Another relation noted in the document of our lives.

That distance is closed, it becomes a relation, it is shared, it is called to account, we are asked questioned and made to comment – made to know. We become an accessory to their exposure to the “worst kind of history.”

Journal Entry: Veiled Distances (October 2023)

(Amended personal journal entry from 2023:)

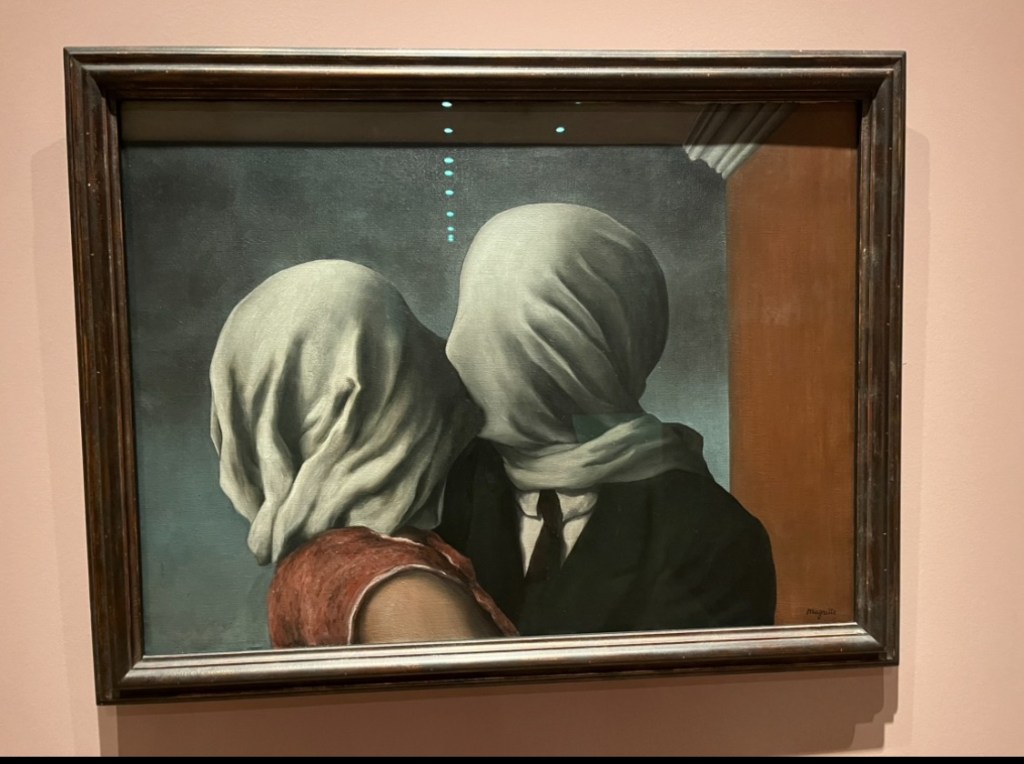

Rene Magritte is often considered a master of misdirection, his detractors tend to claim his work possesses an empty cleverness. I am not interested in art criticism, but in fact an encounter with one work I had while I was with a friend of mine, Cooper Cherry, at the MoMa in 2023.

Again, Magritte’s work often misdirects or, literally, reveals internal treachery. But here, in this kiss, it’s far more strategic. It’s not just witty. I really do think this is an account of love. It is both without place (there is clearly an interior, given the stucco lining, but also a dark exterior, given the background) and completely faceless. And yet there is some kind of contact.

Deleuze and Guattari are wrong about one thing in their engagement with faciality, and this I have learned. The “challenge” is not to “love without a face.” Love is faceless. Love is that which escapes representation and dissolves itself as an institution. Love is that which shatters the edges of the subject function. Love is not something challenged-forth and brought out, love is not the conducting of the lover’s conduct such that this or that relation becomes possible. Such challenges can be left for the police and psychologists. We must understand that, in fact, so long as special being is retained as a foundation of adoration, there is not love. There is only representation. There is an institution and its representation, not love. This contact Magritte gives us is not availed of the operation of the subject. It is an emergence that can only be understood through a negation, without the acquisition of a knowledge.

And what is a kiss if not falling into someone’s eyes so close you can no longer see them, so as to only feel your lips inasmuch as you are encountering theirs? They are greeting each other in their “estrangement.” They are unknown in this intimacy, and, we, with our thirst to say everything an exhaust them (know them from our and their subject position), as voyeurs, are left before them as examining captors. We are left to interpret and know their love. They, however, are not lifting one another’s veils.

I would like to thank everyone who participated in the Friendship reading group.

And those with whom I have shared my Annoyance.