Introduction: A Tenuous Thread

It is difficult to overstate the complexity and vastness, as well as the delicacy and modesty, of Giorgio Agamben’s twenty-year research project, Homo Sacer. What seemingly began as a book meant to examine the relation between the ontological structure of the polis and its (excluded and annihilated) components ultimately expanded to the realms of theology, the metaphysics of actualization, theories of political constitution and Right, and ultimately doctrines of ethos and the use of the body. It is a work that begins in the agora of Athens and passes through the liquidation centers of Aktion T-4 and the camps of Auschwitz.

Upon first scanning across the nine volumes that constitute this daunting work, one may come to the conclusion that there is a sort of meandering present in Agamben’s genealogy, considering it will often swing from topics as vast as the relation between the Kantian imperative to the Nietzschean “will” to an obscure hidden “debate” between Walter Benjamin and Carl Schmitt. However, even with this wandering, such an assertion would ultimately be ill-founded. Agamben’s work is a genealogy in the most stringent Foucauldian sense. It is a gathering up of vast swaths of “subjugated knowledges,” of discourses and developments that have been swept aside from the picture (even though the cannons are still firing) (Foucault 2003, 5). The wandering that occurs in the analysis is as central to the ethic at the core of the project as any other stated commitment within the volumes.

If Michel Foucault[1] was interested in the “blood that has dried on the codes,” Agamben wants to investigate if the ink of those codes may not be infused with the blood of a prior violence. Foucault, in his 1976 lecture “Society Must Be Defended”, described genealogy as an “insurrection” of constituted knowledge through the gathering up of subjugated, quieted discourses. Foucault describes genealogy as a counter-stroke against “functional coherences” and “formal systematizations” that raises up historical content that has been “buried or masked” (Foucault 2003, 7).

When one takes a distanced look at his work, this is precisely what Agamben is doing. While his zones of inquiry and objects of focus may be vast and his analyses often very specific, there is one continuous thread. It is a thread of analysis that is often understated strategically. It is understated because it is, in fact, its overstatement, its metaphysical overdetermination, that Agamben quietly attests has brought modernity to “the nomos of the camp”. The thread that ethically guides, and even alters, Agamben’s path throughout his work is, when stated plainly, this: the evocation and intelligibility of “life.”

What is at stake in Agamben’s work is how life is separated from that which gives it its form and utilized as a means of political circumscription. This can take the form of mobilization, biopolitical security, the claim of sovereign Right, etc. But this is always the thread that runs through Agamben’s work. He is always examining how human life is rendered intelligible (and is put at risk) through the constitutive inclusive exclusion of “bare life,” even in works as disparate as Opus Dei or State of Exception.

Pulling on this thread certainly, itself, would amount to a scholarly achievement. However, if we are to focus on the violence both historical and ontological (this project seeks to show these are not distinct territories), we must look elsewhere. For there is another, almost completely unaccounted, thread in Agamben’s work that makes the disaster of history Homo Sacer unfolds possible. Beneath Agamben’s examination of the metaphysics of actualization is a deeper, darker, anthropological machine at work. It is an apparatus that posits within the human being within a circumscriptive position oriented around capacity as such. We will argue that an analysis of Agamben’s Homo Sacer would remain fundamentally incomplete (from its account of bare life, to constituent power, to “use”) if it did not have, even if hidden, in its center, the historical metaphysical production of disability. The metaphysics of operativity, and the politics it sets forth, defines the conditions and the threshold of what it means to constitute a human being. Agamben’s genealogical engagement with the status of potentiality in the history of philosophy is inseparable from the problem of bare life, constituent power, and the anthropological “machine.”

The tenuous thread that runs through all of these is the problematic of the human, the empty and mobile autarchy that it establishes, and how its policing has defined the political history of “the West.” If Walter Benjamin rightfully asserts that the tradition of the oppressed teaches us that the state of exception is the rule, Agamben’s genealogy seeks to give a strategic and ontological account of the conditions of that tradition.

We will not offer a complete re-examination of Agamben through the lens of disability, though this would be extremely valuable – although one should always be skeptical as to whether one can ever provide a complete analysis of works such as these. We, instead, more modestly will pass through several key concepts and show how an account of disability strengthens their connection throughout his works and provide a new critical (ethical) comportment towards his work.

Another cautionary note about the limit of this project is that notions of abnormality and disability are always discursively constituted historically, and are mobile. The focus must remain on the autarchic predicates of what “constitutes” the human, and therefore the political human. So while we may not always be inserting words connoting contemporary modes of pathologization surrounding it, that autarchy is nonetheless functioning.

First, the distinction between bare life and politically qualified life must be examined through the lens of the autarchy of the human. The inclusionary exclusion of bare life (zoē) in the polis. How bare life is rendered intelligible, then distinguished as an isolated and manipulable object, sets the course of one of the primary claims of sovereign power. As Agamben attests, “the production of bare life” is the “original act of sovereign power” (Agamben 1998, 83). However, by focusing in on different passages in Aristotle’s Politics than those selected by Agamben, bare life (zoē) is exposed as the threshold of what it means to be an animal with an added “capacity” for politics. Aristotle does not merely circumscribe a place for politically qualified life (the proper “posture” (orthos) of political animals), he equally outlines what aligns with bare life (Politics 1254b 28-30). Simply put, zoē will be aligned with the elements of political existence that are to be excluded, but nonetheless politicized. What must also be examined is what it means to be “reduced” to bare life. The distinction between bare life and politically qualified life sits at the core of the very question of politics for Agamben, and situating that distinction at the level of the local-ontological autarchy of the human itself adds a needed perspective.

Then, we will examine Agamben’s engagement with the concept of “constituent power” or the constitution of a political multitude. This is where we find Agamben at his most polemical. Agamben is extraordinarily critical of the notion of a political constituency – one that remains active throughout the ages and always refers back to a moment of constitution. The constitution of the polis is directly related to his delineation of bare life in the early volumes. With a careful reading of sections in Stasis and The Kingdom and Glory, one will see precisely how constituency operates through an exclusive inclusion of politically unqualified life. Everywhere one finds what is supposed to be a constituent force, one only comes up against a constituted power – police and the state. Constituent power finds its footing in a metaphysical principle that always demands an absence of that which is not congruent with it. Any claim back to constituent power is always grounded in an ability to claim an outside, either for the sovereign or for those who are excluded. In theories of political constitution as disparate as Rousseau’s and Hobbes, there is a shared circumscriptive gesture that grounds the very possibility of a political subject. Disability overlaid on these political gestures reveal just how this machine of the anthropos operates.

Agamben himself finally arrives at an extensive description of the autarchic structure of the human being in the final volume of the Homo Sacer series, The Use of Bodies. But it is in a modest monograph on the tale of Pinocchio, a marionette missing its threads, where Agamben tucks away a crucial key to the neutralization of the anthropological machine and the apparatus of disability (which are always working in tandem).

Life Laid Bare: On the Exclusion and Politicization of the zoē

In a lecture he delivered at the Collège de France in January, 1981, Foucault began to layout the task of his work on subjectivity that sought to analyze its continuities and transformations from the Greco-Hellenic age to the advent of psychoanalysis and contemporary psychiatry. As he weaves through the Greek arts of existence, he pauses to remind his listeners and students that…

…for a Greek there are two verbs that we translate with one and the same word: “to live.” You have the verb zēn, which means: to have the property of living, the quality of being alive. Animals live, in this sense of zēn. Then you have the word bioūn.

(Foucault 2017, 34)

Foucault, later in the lecture series, will go as far as to say the bios is as close as one can get to a conception of “Greek subjectivity” (Foucault 2017, 253-254). If Foucault was engaging with these terms as verbs, in their activity, Agamben will, 20 years later, treat them as foundational nouns: bios and zoē.[2] This is the distinction upon which the entirety of Agamben’s investigation into the homo sacer—that life which can be killed at any single time, but never sacrificed—begins. Agamben describes how this distinction operates with the same simple lucidity as Aristotle in Politics. “[S]imple natural life is excluded from the polis in the strict sense, and remains confined […] to the sphere of the oikos” (Agamben 1998, 2).

The sphere of the oikonomia is the private realm of personal reproduction in the Greek polis. It is entirely distinct from the realm of politics. This bare life (which has no plural, and is proper to all living things) is foundational in that its absence from the polis marks the emergence of a political life for the human being.

The first community, for Aristotle exists simply for “everyday needs” or for the necessities of existence (Politics 1252b13). They can consist of a single family, who cohabitate for the purpose of sharing meals, finding shelter, and preserving the basics of life. The first community that starts to move in the direction towards the production of a polity is one that exists for “satisfying needs other than everyday ones” (1252b16).

Once these pre-political communities have transcended the limit of need, politics as an art of existence becomes possible. These quotidian needs of bare survival are explicitly not political for Aristotle, though they are certainly implicated in the polis, as the ultimate goal of life is eu zēn. It is this simultaneous exclusion and implication of unpolitical, bare life (zoē) in the qualified, biographical, life (bios) that Agamben situates the Sovereign claim to life. “For we can neither live nor live well without necessities” (1253b24-25). But furthermore, it is worth diving into Aristotle’s Politics with Agamben’s key insight as a theoretical guidepost.

Of course, for Aristotle, a slave has no place in political life. There are various reasons for this, some of which Agamben will take note of in the beginning of The Use of Bodies, others which are purely speculative (like that the mind of the slave does not exhibit a capacity for phronesis). Ultimately, it must be said that Aristotle’s early despicable gesture in Politics is to circumscribe the realm of politics and political subjectivity (bios) to exclude the slave. However, what should be isolated and focused on is exactly what Aristotle’s depiction of a slave is parallel to. It is the exclusion of the slave, and of those other bodies which are not deemed congruent to the polis which founds it. Aristotle introduces the pertinence of a discussion of the apolitical/expendable status of the slave “…in order to see the things that are related to necessary use” (1253b14-15). This “necessary use” ultimately comes down to a question of necessity and production, because if “shuttles wove cloth by themselves” then “masters would not need slaves” (1253b35-39). Ultimately, their very possibility of a biographical life, of the closest thing the Greeks had to subjectivity, bios, is cut off from them. “Life (bios), though, is action, not production. That is why the slave is an assistant in the things related to action” (1254a5-8)[3]. This element, bare life, which must be tended to, is directly tethered to bare necessities. The invocation of the bios must always come with an invocation of the zoē, exclusively because it needs to be excluded. However, there needs to be an additional term thrown into the fray that Agamben overlooks; orthos (stature, posture, the position of the body immanently, etc.).

Aristotle moves forward from his articulation of the bare life of slavery, and his argument that slavery makes the bare life of the population sustainable, with a contrasting description of the body of a slave and that of a “freeman” (1254b32). The body of the animal and the body of the slave are quite close, in that “[f]or in relation to relation to the necessities bodily help comes from both, both from slaves and from domestic animals” (1254b24-26). However, beyond that, there is a key distinction in how the body of a proper political citizen and the body of a slave present themselves. “[N]ature” Aristotle argues, “tends to make the bodies of slaves and free people different”. The body of the slave is “strong enough to be used for necessities”, while the body of the free person is “upright in posture (orthos) and useless for that sort of work, but useful for political life” (1254b28-30). The enslaved person lacks the constituent body of the citizen and is therefore aligned with the necessities that domesticated animals can also tend to.

It is here where a small, but crucial, correction of Agamben’s interpreters is needed. When Agamben speaks of “animal life” and its relation to the human reduced to bare life, he is not arguing that the human being has been realized as an animal, in its original pre-political state, but—more delicately—that bare life is a principle shared by both. Often, bare life is treated as some pre-political reality of the human animal, but bare life is always produced by its separation of life from what gives it its form.

It is only through its separation and exclusive-inclusion from the polis that bare life becomes intelligible as a distinct entity to be tended to, in opposition to politically qualified life. It is not a primordial distinct substance, upon which bios is built. It is only through abjection that these two territories become possible in a local ontology. In one of his earliest articulations of the separation between zoē and bios (written in 1993, two years before the first volume of Homo Sacer was published), Agamben warns against such a reading of bare life. He accuses the French philosopher, Georges Bataille, of having such a reading:

To have mistaken such a naked life separate from its form, in its abjection, for a superior principle—sovereignty or the sacred—is the limit of Bataille’s thought, which makes it useless to us.

(Agamben 2003, 16)

Bare life only becomes possible once political life is isolated from it. It is not tethered to a pre-political existence, which—as has been discussed—Aristotle makes perfectly clear in his delineation of the role of the slave.

Just as the “state of nature” dwells in the condition of the human being on the precipice of entering a state of civil war through crime in Hobbes’s Leviathan, so, too, does bare life dwell in that same human being that must be killed for exiting the united Multitude whose bare life the Sovereign must protect. The sovereign right to kill is directly linked to the condition of bare life within the united Multitude. Agamben describes the condition this way, it is a “…condition in which everyone is bare life and a homo sacer for everyone else” (Agamben 1998, 106).

For Agamben, the right to kill is not “founded on a pact but on an exclusive inclusion of bare life in the state” (Agamben 1998, 107). The claim Sovereignty has is over the isolated life it invokes as an “unconditioned exposure to death” is “bare life” (Agamben 2015, 24). This is the paradigm through which one can understand how the special being of disability becomes possible, as a risk to the bare life of the populace. If everyone has become a possible homo sacer, that is, one can acquire the “capacity to be killed”, it is precisely because—at any moment—one can lose their “capacity for political existence” (Foucault 1978, 143).[4] This is the manner in which “we are all virtually homine sacri” (Agamben 1998, 114-115).

We are all reducible to bare life (which can be killed at any time) inasmuch as our bare life is always an object in need of protection that only the Sovereign can guarantee, this is its pastoral paradox. It is only through this framework that one can understand Agamben’s treatment of bare life and Nazi eugenics. It is through establishing a threshold of capacity in relation to the bare life of the German volk that the massacre of Aktion T-4 becomes thinkable.

Agamben begins working through some of the modern implications of bare life by discussing Aktion T-4, a Nazi eugenics program that targeted disabled people for euthanasia that set the course for lebensborn. Between 1939-1945 300,000 people were euthanized through an order signed by Adolf Hitler, Aktion Tiergartenstrasse 4. The order was signed one month after the invasion of Poland, but was backdated to when the invasion began – signaling that this order was deeply connected to Germany’s broader war. In October, the Third Reich declared that 1939 was the year “of the duty to be Healthy”, but the elimination program was to be historically documented as beginning the same day as the invasion of Poland (Proctor 1988, 177-178). The whole population was to be mobilized, and optimized, for this war. It is in this sense that we can historically situate Ernst Jünger’s metaphysical thesis, that what characterizes warfare after the beginning of World War I is the population’s “readiness for mobilization” (Jünger 1991). The violence of “total mobilization” has no better an instance than in the war waged by the Nazis against supposed “useless eaters.”

Agamben situates himself twenty years earlier, however, and provides an analysis of an influential pamphlet, which was widespread in both the medical and juridical communities. It was written by a jurist Karl Binding and a doctor Alfred Hoche, and entitled “Allowing the Destruction of Life Unworthy of Life”. Hoche and Binding present a complicated case for the transformation of the patient’s right to die (Totungrecht) into the doctor’s right to kill, in the case of “incurable idiots.” Agamben argues that this pamphlet, which would provide the guiding principles of Aktion T-4, exemplifies one of the fundamental tenets of biopolitical modernity. “The fundamental biopolitical structure of modernity—the decision on the value (or nonvalue) of life as such—therefore finds its first juridical articulation in a […] pamphlet in favor of euthanasia” (Agamben 1998, 137).

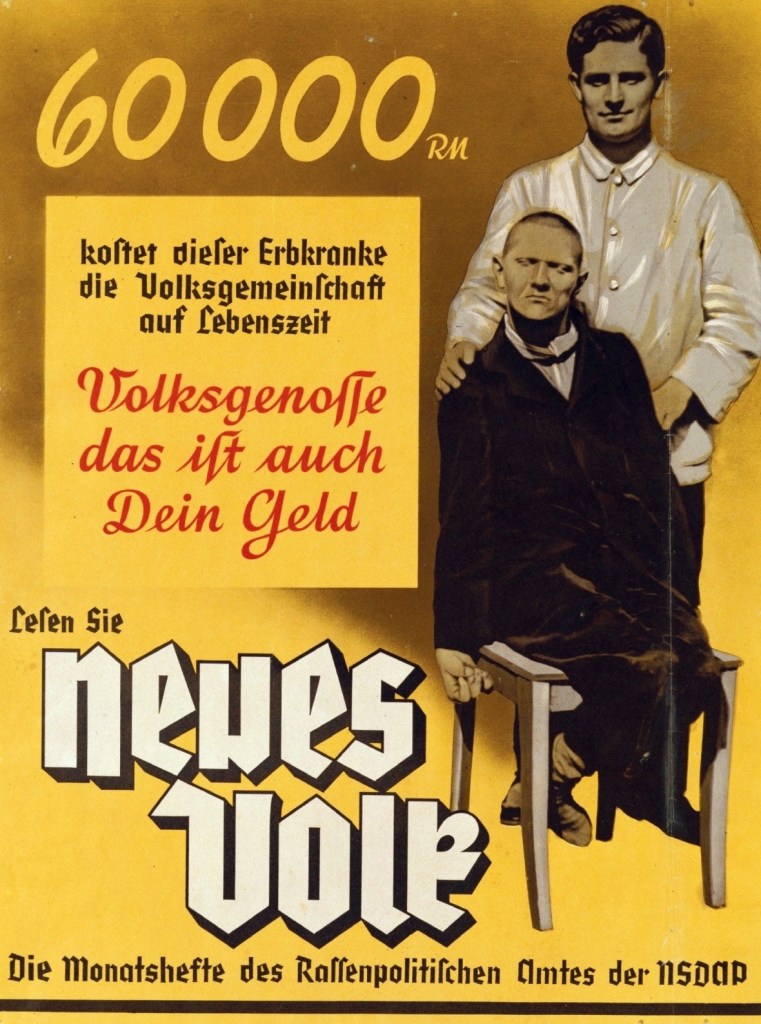

It is worth meditating here on the transformations that must take place in order for a discourse on the “value” or “nonvalue” of life to become possible. The disabled children and adults slaughtered by the regime are reduced to bare life, stripped, and excluded from the political realm. However, in order for this to occur – another transformation must take place. In an infamous poster promoting Neues Volk (a journal published by the Office of Race Policy) read: “60,000RM This hereditarily ill man costs the Volkgemeinschaft (community) in his lifetime/Volkgenosse (friend) that is your money too!” (Fig. 1).[5] The entire population has been mobilized, its bare life must be protected. Because the volk is present only ever as bare life, those “lives unworthy of life” are reduced, in turn, to homo sacer and must be eliminated. It is a dual gesture. On the one hand, the invocation of Volkgemeinschaft holds the entire populace out to a biopolitical limit, where “life” can cease “to have juridical value and can, therefore, be killed without the commission of a homicide” (Agamben 1998, 139). On the other, this presentation of the bare existence of the population demands that those who are deemed a threat must be reduced to bare life and eliminated accordingly. Agamben’s attestation that all have been transformed into bare life is not some reactive polemic against modernity. Instead, it is an articulation of the political conditions necessary for the liquidation of peoples and forms of life.

Perhaps this insight changes the way in which one reads Primo Levi’s poem, “If This is a Man.” We should not read this warning from Levi as an attestation of an inhumanity of the victim in the camp, but rather of the violence that underlies the decision of what constitutes a qualified political life (bios).

Agamben’s investigation into bare life quietly reveals the active danger in discussions of a positive, sovereign, constituted subjectivity.[6] It always presents a mobile exception, a threshold or criteria of possession. These criteria, rather than simply being qualities of qualified life, are, in fact, what make it possible. The shadow of the camp haunts our modern quotidian life, the silhouette of the “Muselmann” haunts every “citizen.” Those murdered are not “bare life” manifest. It is the autarchy of the human being that pretends, with the eyes of a doe and the fangs of a wolf, to ask the question “is this a man?” It sets in motion the course of a disastrous history that can arrive at a “man who dies because a yes or a no” (Levi 2013, 1).

Who Constitutes Constituent Power?

The notion of “constituent power” can be found in political thought at least as far back as Suarez and Hobbes through to Walter Benjamin and Hannah Arendt. However, its fullest articulation is provided in Antonio Negri’s Il potere constituente. In this work, Negri opposes constituent power to “constituted” power. If constituted power is the existing constitution and its enforcement, in a kind of stagnancy, constituent power is, instead, dynamic and always in force. However, it is also something that testifies to an event, to an agency or an act. “The concept of constituent power is the constituent event, the absolute character of what is presupposed, a radical question” (Negri 1999, 16). This event is always active, and always present. Agamben’s critique of constituent power is one of the crucial elements of the Homo Sacer project. “Negri cannot find any criterion, in his wide analysis of the historical phenomenology of constituent (originally translated as “constituting”) power, by which to isolate constituent power from sovereign power” (Agamben 1998, 43).

Agamben’s position is simple: that constituent power is not only a fiction, but the very metric by which the state of exception is declarable. It is that “presupposition,” that claim of a constituent force, that enables a sovereign to suspend the constitution (constituted power) in order to uphold its constituent principles (so that it remains in force). Far from this producing a scenario where constituent power runs in opposition to sovereignty, sovereignty can make quick use of it. Constituent power, rather than simply being an underwriting force of revolutionary activity, is held equally in the hands of those instituting law and those preserving it. Agamben writes this:

Just as sovereign power presupposes itself as the state of nature, which is thus maintained in a relation of the ban with the state of law, so the sovereign power divides itself into constituent power and constituted power and maintains itself in relation to both, positioning itself at their point of indistinction.[7]

(Agamben 1998, 41)

While Agamben focuses on the structure of sovereignty in relation to constituent power, our analysis will instead focus in on the subject of constituent power, and the exclusion it depends on. Negri is right to contest the claim that constituent power’s force is based on its “absence” (Negri 1999 12-13). However, constituent potentiality is always predicated on a particular enforced absence. It is based on an exclusion prior to the constitution of the sovereign.

Though Negri insists that there can be no theory of constituent power congruent to conventional sovereignty, an analysis of how the multitude comes together in Leviathan—accompanied with an account of disability—reveals otherwise. That the constituent gesture itself conjures up disability to exclude it, prior to the personation of the multitude or the passage of the general will to the sovereign, reveals another angle for a critique of biopolitical modernity. It also exposes how constituent power is not a force persistently working against sovereignty, but rather an exception that is ontologically prior to sovereignty itself. Constituent power is always tending towards sovereignty; in that it demands a constituent subject that will serve as the basis of the production of the sovereign. In all different ways, this is found equally in Hobbes, Spinoza, and Rousseau.

One helpful way to provide a description of who Negri believes to be the “constituent subject” is to start with his reading of Foucault. Admittedly, it may seem strange at first that Negri chooses Foucault, whose genealogy of the entrance of vitality into politics sets the tone for his work on biopolitics, as a launching point for his theory of the constituent subject. Negri, however, provides a strategic misreading. Negri inserts a distinction between biopower and biopolitics – a distinction Foucault himself does not articulate. Biopower, for Negri, seems to be simply sovereign power over life. However, biopolitics is a movement by which “the subject goes back into itself and rediscovers a vital principle” (Negri 1999, 28). While this is a complete misapprehension of what is actually occurring in Foucault’s account of biopolitics and its relation to the subject, with the twisting of the knife being that a radical opposition can be found through a “rediscovery” of the self, it does in fact brilliantly articulate the actual problem of constituent power. Constituent power is a vital force, directly aligned with production. “The political is here production, production par excellence” (Negri 1999, 28). This recognition of the need to isolate a vitality within a political constituency, and to place it inside the apparatus of production is the principle of biopolitics; it is what makes the protection of bare life a governmental imperative. To have mistaken this “vitality” as a tool of revolt, rather than the condition of abjection, is the limit of Negri’s thought.

Standing in the wake of the failure of the movimento del ’77, Negri seeks to reconceptualize the political subject. He settles, in Il potere constituente, on the “adequate subject.” The adequate subject takes the form of whatever has the “strength” and “constitution” to produce “constitutive trajectories.” Negri’s historical task is to identify in the adequate subject “the terrific metaphysical effort to propose constituent power as the general genealogical apparatus of the sociopolitical determinations that form the horizon of human history” (Negri 1999, 33).

Our task, alternatively, is to identify in this adequate constituent subject “the terrific metaphysical effort” that constitutes the exclusionary gesture that is the formation of constituent power. Of course, the very notion of a multitude defined by “adequacy” should immediately register concern. However, one must go further. By examining the position of the disunited multitude in Hobbes and the passage of the general will to the sovereign in Rousseau, the autarchy that constituent power simultaneously needs and makes possible can come into light.

In his third volume of Homo Sacer, Stasis: Civil War as a Political Paradigm, Agamben isolates the disunited and dissolved multitude in Hobbes’s Leviathan and De Cive as worthy of deeper treatment than is generally given – even by Hobbes himself. According to Agamben, the dissolved multitude “not only pre-exists the people-king, but (as a dissoluta multitudo) continues to exist after it. What disappears is instead the people, which is transposed into the figure of the sovereign” (Agamben 2015, 47). If the dissolved multitude (as the disunited multitude) pre-exists the sovereign, then this “unrepresentable” body must be examined. Agamben argues that the dissolved multitude is the object of biopolitics, and can only be “represented indirectly” through the empty city, filled with guards and plague doctors, beneath and outside the sovereign. If Agamben’s thesis is correct, and this disunited multitude precedes the sovereign, then the ontological operation by which that disunited multitude disappears into the figure of the sovereign warrants our attention.

In order to understand the way in which the people disappear, leaving only the objects of biopolitical intervention, one must break down Hobbes’s process by which a sovereign is authorized. The sovereign, for Hobbes, is an artificial person. He distinguishes between an artificial person and a natural person by the attributability of words or actions. A natural person is someone whose words can only be attributed to them. An artificial person is one who represents the words and actions of another. Hobbes provides a succinct depiction of who can be an authorizing figure. “Of persons artificial, some have their words and actions owned by those whom they represent. And then the person is the actor, and he that owneth his words and actions is the AUTHOR, in which case the actor acteth by authority” (Hobbes 1994, 101). To “personate is to act or represent himself or another.” Inanimate objects can, in fact, be personated – like an overseer of an estate or a manager of weapons. They can be authorized to act on behalf of those entities.

There is an exception, however, “things inanimate cannot be authors, nor therefore give authority to actors” (Hobbes 1994, 102-103). Crucially, Hobbes presents a list of those who are inadequate and cannot authorize. “Likewise, children, fools and madmen that have no use of reason may be personated by guardians or curators can be no authors” (Hobbes 1994, 103). The very gesture that constitutes the presence and power of the fleeting united multitude is the same one that produces the exception. The movement that identifies the elements that come together in the disunited multitude, with its constituent potentiality, is the same movement that establishes an autarchy. In chapter XXVI law is described as a “command” put forth by the author, but enforced with the sword of the actor, the sovereign (Hobbes 1994, 176-177). The sovereign is the person of the united multitude. Hobbes is keen to remind his reader, however, that this “unity” is the result of the “unity of the representer, not the unity of the represented,” and it is this that “maketh the person one” (104). What, then, is the status of these non-authorizing bodies, who supposedly do not hold the quill that pens their own condition?

Their status is one of perpetual paradox. Hobbes writes, “Over natural fools, children, or madmen there is no law, no more than over brute beasts; nor are they capable of the title of just or unjust, because they had never power to make any covenant” (177). This position of transferred authorization to an adequate subject gets further complicated when one accounts for Hobbes’ definition of the right to prevent one’s own bodily harm. In chapter XXVI Hobbes lays down his basis for the sovereign’s right to punish – which is relinquished in the state of nature and yet retained in the person of the sovereign himself. Though the members of the disunited multitude relinquish their right to punish, they have not relinquished their right to defense. Hobbes writes that “no man is bound by covenant not to resist violence; and consequently, it cannot be intended that he gave any right to another to lay violent hands upon his person” (203). However, in their entrance into the commonwealth, “every man hath given away the right of defending another” (204). Authorship is transferable for those deemed inadequate, but the right to defense is explicitly not. And it is necessary to remember that “harm” to those who have revolted is not done by the right of punishment, but rather by the right of war (205). This is the condition of the homo sacer. It is a life that is simultaneously outside the law, but subject to destruction nonetheless. Even more fascinatingly, if our reading of Hobbes is correct, the establishing of this exception surrounding “fools” and “madmen,” occurs ontologically prior to the unification of the multitude as it disappears into the people-king of the sovereign. Therefore, even if we grant Negri the grace to say constituent power is not automatically in the hands of sovereignty, the exclusion necessary to make the constituent gesture possible produces both the conditions and the object of the state of exception. It is in this way that constituent power is an absence, it is an absence of the eternally excluded (yet nonetheless included) party – those who are not “adequate.”

This same tenuous thread is present in the presentation of constituent power Negri found in Rousseau. Negri correctly laments that Rousseau’s concept of the general will has produced a “muddled web of definitions” (Negri 1999, 204-205). One has to wade through, carefully, the distinctions Rousseau makes between Sovereign/State and Citizen/Subject in order to grasp the way in which the force of the general will moves through his political ontology. Negri argues that it is this muddle that produces a series of juridical documents, like the Declaration of the Rights of Man in 1789, which would constitute the “skeleton of constituent power” (204).

Foucault, in a lecture at the Collège de France in 1978, tells his listeners that the introduction of the general will into “political science” does not eliminate the problem of sovereignty, but makes it “more acute than ever” (Foucault 2007, 143). Agamben’s reading of Rousseau coincides, in a very particular sense, with Negri’s. Agamben sees in Rousseau’s general will an attempt to naturalize legislative activity. Agamben writes this:

The sovereignty of the law, to which Rousseau refers, imitates and reproduces the structure of the providential government of the world. Just as in Malebranche, for Rousseau the general will, the law, subjugates men only in order to make them freer, and in immutably governing their actions does nothing but express their nature. And just as in letting oneself be governed by God they do nothing but let their own nature take its course, so the indivisible sovereignty of the Law guarantees the coincidence of the governing and the governed.

(Agamben 2011, 277)

The law that subjugates in order to let nature “take its course” is inseparable from the discourse on natural inequality that is occurring throughout Rousseau’s work.

In order to delve into this, though, a brief articulation of the political ontology of the general will is needed. The “public person” of governance in Rousseau is split into two. The first being the sovereign, which is the active element and, because it is the recipient of the general will, has lawgiving power. The second is the state, which is passive in its reception of lawgiving power. Individual persons, “the associates,” are broken down into two parts as well (Rousseau 2011, 165). The active component being the citizen – which participates in sovereign power through the general will, and is its vital base. The passive component is the subject, which is regulated by the state through the reception of punishment. The subject is the object of law-preserving violence.

The actualization and protection of the general will is the primary function of sovereignty for Rousseau, which is what makes it indivisible. The realization of this will though, and the social question it posits, when understood through Agamben’s argument that the law enables the human to “express their nature”, returns us to the question of the constituent exception and the autarchy of the political human being. In his discourse on inequality, Rousseau prods his reader with a question. “Why is man alone subject to becoming an imbecile?” (Rousseau 2011, 53). Rousseau sees in the problem of social inequality a deeper danger than the mere squalor of proletarian or lumpenproletarian existence. The human being risks losing its perfectability. In losing this theodicy of perfection, the human being is no longer able to truly express its nature. However, inequality is “practically nonexistent in the state of nature” (Rousseau 92, 2011). The problem of natural inequality and social inequality is only possible in a world of property and law. Rousseau argues this:

[I]t follows that inequality in status, authorized by positive right alone, is contrary to natural right whenever it is not combined in the same proportion with physical inequality: a distinction that is sufficient to determine what one should think in this regard about the sort of inequality that reigns among all civilized people, for it is obviously contrary to the law of nature.

(Rousseau 2011, 91)

This distinction between natural inequality and political/moral inequality is crucial, though. The problem is that social inequality can produce or—worse—be conflated with natural inequality. Natural inequality is established by “bodily strength” and “qualities of the mind or soul” (45). Moral/political inequalities are privileges enjoyed at the explicit expense of others.

The lamentable despotism of moral inequality is that it can result in a world where it is acceptable for “an imbecile to lead a wise man” (92). The role of the sovereign, and the protection of the general will can be understood in a different way with these concepts in mind. The autarchic structure of the human being is maintained by the general will as it is expressed through the sovereign. Moral equality must replace natural equality, so that natural inequality becomes intelligible. The Declaration of the Rights of Man and Citizen, which Negri believes to be among the first expressions of this constituent power, echoes this sentiment in the very first article. “Men are born free and equal with respect to their rights. Civil distinctions, therefore, can only be founded on public utility.” The autarchic structure of the human, inherent in constituent power, demands regulation by the state because of the risk of degeneration. The Person, as a participant in the general will, carries their bare life in the passage of that will to the Sovereign, who, through the State, maintains the dividing line between natural and moral inequality.

Constituent power is the exception in force. It is not just the condition that makes it possible, as Agamben tactfully argues, for a sovereign to declare a state of exception. Constituent power, in order to even come into force, has to attest to an absence of those elements of human existence that make it possible. The Multitude of Michael Hardt and Antonio Negri is only an adequate subject in that it gives inadequacy its name, and casts it away (while retaining it in its exception). The question of constituent power always asks us the question of who constitutes the constituent subject. No matter how one answers, the trap of the sovereign exception is laid. It is in this way, without intending to be polemical, that one can call constituent power, properly speaking, a theory of able-ism.

Conclusion: The Marionette with(out) Qualities

After 20 years, Agamben would finally end his investigation into the figure of the homo sacer, the protagonist of his research. In The Use of Bodies, Agamben makes a blunt attestation about the consequences of the route that political ontology took, from Aristotle to Arendt. “Political life is necessarily an autarchic life” (Agamben 2015a, 198). Because this term has floated throughout this investigation of Agamben, it is now time to discuss it. Autarchy is a founding principle of politics because the human being, set aside for their production of a polity, is an exceptional, special, being. The species-being of the human being that has dominated reactionary and revolutionary politics alike, must be neutralized. However, to do this, the apparatus of disability must be rendered inoperative. It must cease to make these metaphysical distinctions, to divide life. Disability is an apparatus of distinction that makes possible the special being of the human being. The human being, as the master of potency, throws itself into its own violence by making of the world an image of realizable power.

So long as the human being is an exceptional entity that sits at a threshold defined by its capacities, the reduction of life to bare existence will continue because life will always be separated from the form it takes.

Though the Homo Sacer investigation ended in 2014, one could argue there is a “secret” appendix hidden in a small book written several years later. It is a monograph on the tale of Pinocchio. While one might be hesitant to shift from political and philosophical insights over to the realm of the literary, it is important to remember precisely where Agamben has always situated his own work. “I am perhaps not a philosopher but a poet, just as, conversely, many works that are thought to be literary instead rightfully belong to philosophy” (Agamben 2024, 87). This book on Pinocchio is a literary text that rightfully belongs to philosophy. However, more specifically, it belongs to the trajectory of Homo Sacer. Agamben follows the young(?) marionette as he takes on, and flees from, the predicates that made him a boy. Agamben sees in this intransigent puppet without strings a surface upon which the most violent of presuppositions about the human are projected:

Pinocchio will thus be a paradigm of the human condition, because—even if it is not clear who is to hold the strings that make him move and whether there truly are these strings—he is condemned, as his adventures eloquently show, to be always inferior and superior to himself, never to reach a secure identity.

(Agamben 2023, 56)

Pinocchio is always inferior and superior to himself, neither boy nor marionette. He will always be in that zone of tension, unable to reach an identity. This is precisely the condition of the human being that the exception of politics has laid out. Disability, as an apparatus, terrorizes and simultaneously secures the exception of the political animal we call “humanity.” The human, always striving and toiling with the apparatuses that capture it, remains draped in its inhumanity.

References:

Agamben, Giorgio. 1998. Homo Sacer: Sovereign Power and Bare Life. (D. Heller-Roazen, Trans.) Stanford: Stanford UP.

__. 2000. Means without Ends: Notes on Politics. (V. Binetti & C. Casarino, Trans.) Minneapolis: Minnesota UP.

__. 2011. The Kingdom and the Glory: For a Theological Genealogy of Economy and Government. (L. Chiesa, Trans.) Stanford: Stanford UP.

__. 2015. Stasis: Civil War as a Political Paradigm. (N. Heron, Trans.). Stanford: Stanford UP.

__. 2015a. The Use of Bodies. (A. Kotsko, Trans.) Stanford: Stanford UP.

__. 2023. Pinocchio: The Adventures of a Puppet, Doubly Commented and Triply Illustrated. (A. Kotsko, Trans.) New York: Seagull Books.

__. 2024. Self-Portrait in the Studio. (K. Attell, Trans.) New York: Seagull Books.

Aristotle. 2017. Politics. (CDC Reeves, Trans.). Indianapolis: Hackett Publishing Company.

Foucault, Michel. 1978. History of Sexuality Volume 1: An Introduction. (R. Hurley, Trans.) New York: Pantheon.

__. 2003. “Society Must Be Defended”: Lectures at the College de France 1975-1976. New York: Picador.

__.2017. Subjectivity and Truth: Lectures at the Collège de France 1980-1981. (G. Burchell, Trans.) New York. Picador.

Hobbes, Thomas. 1994. Leviathan. Indianapolis: Hackett Publishing Company.

Junger, Ernst. 1991. “Total Mobilization.” In R. Wolin & J Golb, Eds. The Heidegger Controversy: A Critical Reader. Cambridge: MIT Press. 119-139.

Levi, Primo. 2013. Survival in Auschwitz. (S. Wolf, Trans.)

Negri, Antonio. 1999. Insurgencies: Constituent Power and the Modern State. (M. Boscagli, Trans.) Minnesota: Minnesota UP.

Proctor, Robert. 1988. Racial Hygiene: Medicine Under the Nazis. Cambridge: Harvard UP.

Rousseau, Jean-Jacques. 2011. Basic Political Writings (Second Edition). (D. Cress, Trans.) Indianapolis: Hackett Publishing Company.

[1] Who Agamben is most deeply indebted to in Homo Sacer.

[2] For the time being, Agamben’s supposed “correction” of Foucault will be set aside, as ultimately it is not material to the analysis. Though there has been much academic clamoring about it in the last two decades.

[3] Emphasis my own.

[4] This is, perhaps, the “correction” of Foucault that Agamben alone makes possible.

[5] “60,000RM kostet dieser Erbkranke die Volksgemeinschaft auf Lebenszeit/Volksgenosse das ist auch Dein Geld”

[6] This is precisely why Agamben believes the notion of Dasein, which comes so close to conventional subjectivity, is ultimately betrayed if one begins to speak of it as such (Agamben 1998, 188).

[7] Again, originally, “potere constituente” was translated as “constituting power,” the more accurate translation is “constituent power,” which is an addition of my own.