Letter to a Harsh Friend:

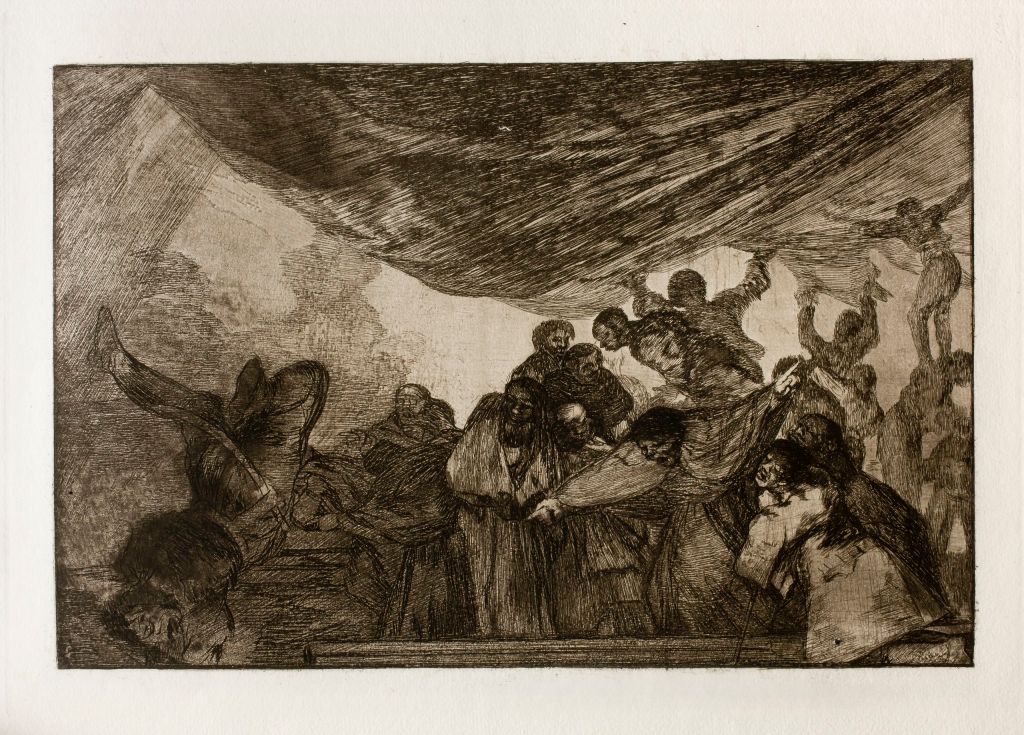

It is said that we are simultaneously resigned, and yet the great antagonists of philosophy. We admit we are no friends of the history of philosophy, that is certainly true. We do not take the blackmail of the enlightenment to be given unities that are to be left untouched. We have the audacity to submit a priori notions to history because we refused to be torn from it. We call out from the graves of the vanquished and will not leave their side – because we, just like our supposed good faith critics, cannot. We are in the ruins of history, but because we recognize this disaster as such, we are villains tearing at the façade of the parlor and dragging our indignant claws along its cheap wallpaper.

Disabled philosophers are among the philosophers to come, who do not treat the criticism of species being, the giveness of the unified subject, and eugenics as a mere inconvenience. But they are not here to be taken seriously, not by the likes of those who still call themselves “rationalists” or “progressives”. Disabled philosophers are conceived of as outside, in the “wilderness” as one critic of Shelley Tremain called us, but we have always lurked within. Our error is to have never groveled for a place within the false circumscription of those who have the Right to speak of, and to, the logos.

It is said that we are the enemy of the concept: this is wrong. Of course, the only way it could be a truth is if the concept could only be understood through identity, normalization, Gestell, or an apparatus of control (all of which are, of course, concepts). We, in fact, do nothing but proliferate concepts – in hopes that one will be a brick to hand to those who are striving to live differently. There is no point in being an enemy of the concept, because it necessarily fails. This is its liberating tragedy. Instead, the coming crip philosopher understands their place en medio in the history of philosophy and of the concept, and begins to disentangle and pry apart the unities that have given these concepts their stability (the rational subject, Right, the necessity of power, value, use, utility). In doing so they posit new concepts, which will come in ephemerally, flash, and fade. They will leave an outline of the intolerability of this world, though, this is the difference. Whereas those who have truly resigned (to the history of philosophy, and its malignant demand to find the good power) will only ever work tirelessly to ground the necessity of this terror.

Those who call us “resigned” are doing nothing but demanding we recognize metaphysics as a science of innocence. But we indignant disabled philosophers know better than to respond to this. Their lamentations are nothing more than a quiet demand we lay down some constituent point – some formal necessity of rationality, utility, economy. Only philosophy littered with subjective presuppositions does this, only dogmatic Images of thought. What our “critics” are doing in their polemics is thinly masking a shame: a shame that one cannot mobilize their way out of war, that one cannot economize their way out of capitalism, that one cannot produce a counter-Leviathan that initiates the end of human prehistory. They demand we recognize that philosophy, in the end, has always been right, and tending towards the good – that the disaster of history is merely the necessary. Any resistance to the “goodwill of thinking” or the dogmatic image of thought that defines the history of philosophy should be deemed in their eyes as nihilistic resignation. We are not afraid of resisting the necessity of “reason” – we are not “disciplining” reason. As any Kantian should know, reason itself is discipline. For the rationalist, one obeys reason, so that it is properly used within its confines.

The ableism of rationalism is well-established, but well-established because it can always contort itself – like any exception, it is mobile. Our critics are quite clear about what they think of us having the audacity to point this out. If we resist “reason” as a given unity and necessity, we resist history, if we resist history, we resist progress, if we resist progress, we are nihilists. Our resistance is to be ignored, delegitimized. It is a good thing, then, that we are not seeking legitimization. Struggle, for them, is always to be gathered up and shoveled into the engine of “progress”. We are searching, instead, for pathways to the emergency brakes.

They attest rationalism “is good again”1, they look at the crip and say, “we have a place for you now.” And it is the exact same place. This is no different from the Negriists who extended the expanse of the economy to every facet of existence and called it liberation – because who wouldn’t want to be a part of the true movement, who wouldn’t want to be properly proletarian? This extensionism is merely the whining that comes from refusing to refuse – of being bound up in the false negation. We, instead, are the negation of the false negation. But our critics demand we take their quest to take and ground power seriously, and that we sit silently in our indignant foolishness. But we will lovingly mock them as King Lear’s fool mocked him:

“I am a fool. Thou art nothing.”

This is the ultimate anxiety of the metaphysics of power. Nothing. That it is nothing. We engage with metaphysics to neutralize it. They engage with metaphysics to ground power. But we recognize that their claims are empty because the throne is empty.

We will admit that we have ill will for academia, for the history of metaphysics, for increasingly stale theories of constituent power. However, it is not just because, as Agamben says, that they are fictions (and they certainly are). Instead, we work against these blood-stained motifs because they form a tale of the hygienics of civilization – which we have attempted to articulate time and time again. We will continue to do so, even if we continue to fail, because living/thinking differently is not a question of success but of endurance and overcoming.

Our critics turn to us and say that we are ungrateful to the history of philosophy – which has now supposedly “solved” for the violence of panopticism, psychiatric power, and the game of normalization by incorporating abnormality into a dialectic of identity and difference. But there are two problems with this. Abnormality has never been a negation of the norm – it is its condition and the basis of its technologies of intervention. Abnormality is not in a dialectical relation with normality – because normality is empty. It is nothing. The eugenic discourse that is openly hidden (intolerably obvious) within the history of metaphysics, a discourse that must be unraveled, is not simply one part of a dialectic. Ultimately the biggest problem with those who demand we see ourselves as resigned, and sit down in our place, is that they do not engage or confront what is before them – and instead opt to resort to tired reliance on the same cold rationalism of the necessary and secondhand criticisms of those who have tried to break free from the thinking of technological/commodity/eugenic modernity.

Finally, our critics argue that our preoccupation with the neutralization of the metaphysics of capacity and ability is the crux of our resignation – the regulative principle of our self-defeat. We are supposedly “vampires” on philosophy, which we ourselves engage in – beasts drinking our own blood in penance of having spilled it in the first place. This is essentially demanding we be a good house guest to philosophy – that we ourselves participate in it and therefore cannot demean it. While the premise is absurd, it is only the result of a misapprehension of what we are doing. If, in fact, one sees that a critical inquiry into capacity and ability would collapse the entire history of philosophy, we can only say that it is not our problem.

Our critics are not seeking to defend the concept. The concept, as we have stated, is in no need of a defense. Instead, our critics want to defend special being and capacity as the bases of species-being.

The question becomes, then, who is afraid of this destitution?

Conclusion: Indignation and Intelligibility

Disability will not go away. And the genealogy of capacity and ability gathers up these threads and, with the right tact and focus, raises them to a point of insurrection – against the unity of the rational subject and its violence, against the necessity of economy and its violence, against the attestation that the human’s concrete essence is labor-potentiality and its violence. Everyone is a philosopher. We all philosophize. If we do so with guilt, it is not out of a condemnation of philosophy, but out of a call of conscience which says we are guilty – guilty of upholding ableism, eugenic modernity, and the ever-expanding creep of economy. We are “guilty” of not yet thinking differently. Intelligibility is what is at stake in our era. We are fighting over a world dominated by the logic of replaceability, absolute calculability, and the apparatus of disability. All of these are questions of intelligibility. We are here to resist the desert of value, and the eugenic present.

If we resist the logic of compulsory intelligibility, it is because we understand that intelligibility is the technology of the police. Life must be intelligible because it must be manipulated. It must be manipulable because it is isolated only as an object of policing. So, it becomes a problem. Life is perfectly evasive because it is always presented as necessarily intuitable, yet nothing could be further from the truth. Which is why life is only ever conjured up in the hand of power, torn from its form, in the name of evading error.

These are the stakes.

- Foucault, History of Sexuality Vol. 1. “Tomorrow sex will be good again.” We are told we have awaited, and arrived at the new, good, circumscription. ↩︎